Related highlights:

Washington Post does its best to rehab ‘Anonymous’ New York Times author

Pragmatic Obama sees ‘defund the police’ as political poison

—

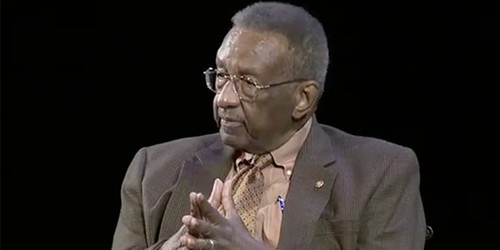

Conservative author and economist Walter Williams has died, ending the illustrious career of one of the fiercest yet most soft-spoken advocates of liberty.

He was 84.

Many conservatives know Williams from his years of subbing for talk radio host Rush Limbaugh. Others know Williams from his appearances on the 10-part 1980 PBS television series Free to Choose, featuring Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman. His George Mason University students knew him as an affable, popular, and brilliant economic professor.

Born in 1936, Williams was a prolific author.

Williams “was the author of over 150 publications which have appeared in scholarly journals,” Economic Policy Journal recalls in its memoriam. His work appeared in Economic Inquiry, American Economic Review, Georgia Law Review, Journal of Labor Economics, Social Science Quarterly, and Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy and popular publications such as Newsweek, Ideas on Liberty, National Review, Reader’s Digest, Cato Journal, and Policy Review.

The man also wrote ten books: America: A Minority Viewpoint, The State Against Blacks, All It Takes Is Guts, South Africa’s War Against Capitalism, Do the Right Thing: The People’s Economist Speaks, More Liberty Means Less Government, Liberty vs. the Tyranny of Socialism, Up From The Projects: An Autobiography, Race and Economics: How Much Can Be Blamed On Discrimination?, and American Contempt for Liberty.

To his friends, Williams, who was born both poor and fatherless in Philadelphia and spent much of his childhood in public housing projects, was known as an uncompromising lover of liberty.

“Walter liked smoking and he also hated the TSA,” economist David Henderson recalled this week after learning of Williams’s death. “Some years ago, the combination of no-smoking [regulations] on planes and intrusive groping by the TSA caused him to vow never to fly by commercial airline again. When he received offers to give speeches that were far enough away that driving was infeasible, he negotiated for a private airplane to take him there.”

John J. Miller likewise recalls in National Review the time that Williams’s exerted his independence and fought racial prejudice after being drafted into the U.S. Army in 1959.

“Although the military had desegregated, he bristled at institutional prejudice — and demonstrated his willingness to challenge racial orthodoxy,” Miller wrote in 2011. “He complained constantly about discrimination, even writing a letter about it to his commander-in-chief, President Kennedy.”

“When he stepped off the plane for a posting in Korea,” Miller continues, “he was told to fill out a paper with personal information. In the box for his race, he claimed to be white. ‘No, you’re not,’ said a warrant officer who reviewed the form. ‘Yes, I am,’ replied Williams, who knew perfectly well that he couldn’t pass for a white guy. Williams explained his choice to the officer: ‘If I checked off ‘Negro,’ I’d get the worst job over here.”

Williams's first assignment ended up being a relatively easy one.

But as he was known for his sharp mind, he was also known for his keen wit, his dry sense of humor, and his kindness.

Personally, however, Williams will be remembered best as the gentle conservative economist who frequently clowned on his late wife, Connie, who died in 2007.

As Marymount University economics professor Brian Hollar recalled after her death, “Professor Williams used to make a lot of jokes in class about making his wife shovel snow, how much he spoiled her, used her bad behavior for illustrating downward-sloping demand curves, etc. You could always tell through his teasing that he loved her deeply.”

Indeed, the Connie anecdotes were indicative not only of Williams’s dry sense of humor, and they acted not only as excellent examples to explain complex economic theories, but they displayed well his humanity. The stories always revealed his clear and deep love for his wife of 47 years.

He will be missed. Rest in peace, Walter Williams.