Heroes, Dark Heroes, and Antiheroes

How audience preferences have changed through the generations

Morning, everyone!

We’re going to do something different today.

Today’s edition of And Another Thing … is an article written and published originally by retired psychotherapist Adam Lane Smith. It’s a fascinating examination of the rise of so-called “antiheroes” and “dark heroes” in popular culture. How did we get here? Why are we here? How do we escape this hopeless, cynical hellscape populated with deadenders such as Scarface and Deadpool?

I found Smith’s analysis of pop culture’s obsession with deeply flawed and irredeemably broken “antiheroes” so fascinating, in fact, that asked his permission to reproduce it here in its entirety.

You can read more about Smith at the following link. You can also view his other writings here.

Enjoy!

–

Much has been made about the oft-lamented shift from Hero to Antihero and the modern obsession with romanticizing evil. Most frequently, I’ve heard this complaint directed at modern western media’s fixation on selecting one unyielding human trash fire after another as every main character. There’s a reason modern book sales and movie sales are struggling.

To understand the shift over the last hundred years of stories and main characters, one must understand the cultural environments and the mental aspects at play, particularly attachment formation and its impact on society.

Buckle up, because we’re going back a full century to where things began.

Author’s note: This article is a deep dive into the last 7 generations, their traumas, the way they’ve viewed the world, how they impacted storytelling, and the way future storytelling may change again. Many individuals will read this and find they don’t fit perfectly into each category because generations are not uniform monoliths. Instead, this article looks at overall generational trends in an effort to predict what the next storytelling audience wants.

Attachment problems on the rise

A hundred and twenty years ago, around the year 1900, family bonds were much more significant and tighter than today. That doesn’t mean every family lived in blissful euphoria, but a person was far more likely to grow up surrounded by grandparents, great-grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, many siblings, and married parents. While dysfunction still existed, the family unit remained strong enough that people could fill the gaps by attaching to healthier family members to nurture their development and grow into healthy, loving, moral people.

They also had little choice but to embrace their family and make things work. In a world without reliable cars or internet or cell phones, family was all you had. That had good and bad aspects, but at least people largely grew up knowing what love was and how it felt. Themes about responsibility to your family and community were huge in their stories.

In fact, the classic hero who upheld virtue simply because it was right, honored his parents, chose a good partner, had children, and strove to embody justice and moral fortitude has played the leading role in the vast majority of ancestral stories. This is because storytelling was originally a vehicle to transmit cultural values. Characters lacking these moral points were not presented as celebrated fictional celebrities, but cautionary tales for young people to learn from.

The Greek storytellers gave every hero a flaw, but this was the one exception to his moral character which provided a weakness for the tension of the story to turn upon. His entire being wasn’t made up of flaws, and he strove to overcome his flaw and become a better man. Only villains wallowed in their flaws or refused to change them. Sometimes the hero succeeded in overcoming his flaw, making him an inspiring hero. Other times he didn’t, leading to tragedy. But he nearly always strove to do what was good for the sake of objective morality.

Much of that changed around the 1920s. World War I left a generation shattered and drifting. We call them the Lost Generation. They were torn from home and sent into brutal combat which by most accounts dwarfs modern warfare in terms of sheer horror.

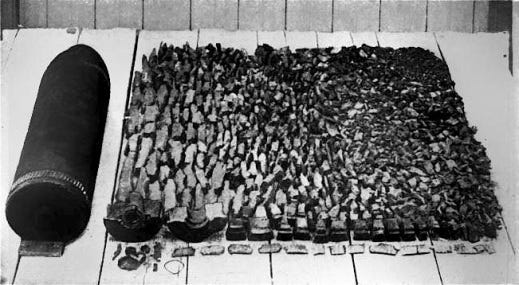

Here’s a WWI artillery shell before and after exploding into more than 7,000 pieces of shrapnel.

Imagine 7,000 pieces of superheated metal striking the ground in front of you, shearing through your hometown buddies conscripted alongside you, and seeing your dearest childhood friends torn into bloody gibbets in a single moment. The shrapnel enters your own body and you carry it for the rest of your life because the doctors just can’t dig out all the metal splinters, so you simply ache forever.

We get terms like “shell-shocked” and “thousand-yard stare” from this era as we learned what PTSD looked like in soldiers, though many initially believed the men were faking it. In reality, many veterans spent the rest of their lives reliving those scenes of carnage over and over.

Which leads to the roaring twenties. Industrialization tore families apart and sent the traumatized young people and their siblings into the cities where they partied without parental supervision. Prohibition came along to curb the excess and just made it even cooler to thumb your nose at authority. As families pulled apart in the drive toward better-paying jobs and convenient living in the cities, people unknowingly traded away healthy attachment formation for themselves and their children. It’s challenging to build a family system based on love and nurturing and wise advice and continuous care when the adults work 12 to 18 hour shifts in factories and come home exhausted, only to wash away their cares in alcohol.

But at least everyone had money and could afford to visit their big families in the country to rekindle some of those relationships, right?

Enter the Stock Market Crash.

Enter the Dust Bowl.

Enter the Great Depression.

Family farms washed away overnight as topsoil blew away in the wind, gutting Middle America. Families clustered toward the coasts to escape starvation and death and wound up in cities, shoved into jobs for low pay because guess what, now the supply of cheap labor just increased and employers could play the market. Parents were shoved into tiny apartments with no yard to raise their nine kids who died from numerous diseases passed around the packed community. Enjoy the stench of sewage in the streets as plumbing struggled to keep up. Try not to starve to death when your arm gets cut off and your employer fires you for being useless. Hope none of your kids gets sick because you can’t afford the doctor bills.

Parents buckled down and developed a whole new kind of shell-shock: necessary workaholism.

“If I stop working, if I slow down at all, my children will starve and die.”

This brings us the Silent Generation: people pushed to the brink, slaving away their entire week in factories and rarely seeing the sunlight. They could remember what it was like having a family, but now that concept was just a bitter memory soaked in loss. They hoarded every rusty nail and broken pipe because they might never get another one, and when they died, they gave these trash hoards to their confused kids as beloved treasures.

During this time we see the rise of a few antiheroes in extreme cases, but mostly dark heroes. Dark heroes take the original concept of the upright moral hero and give them a deeper flaw, something which eats at them far more but which is accepted rather than changed because the emphasis is still on overcoming a greater evil. We accept their brutality because underneath they’ve got a heart of gold, and they still strive for justice and morality. Conan the Barbarian is a good example of a dark hero because he’s still capable of deep love, accepts love from others, and strives for honor (a type of morality) even as he slaughters punks by the score for looking at him wrong. We can still look up to these heroes as good examples of a moral person doing what needs to be done, albeit with a dark side usually caused by trouble in their personal history. This reflects the Lost Generation doing what needed to be done and sometimes sacrificing their principles and personal happiness for the sake of the greater good.

This era leaves us with parents buckling down and struggling to survive, raising their hungry children in cramped apartments. Family structures have collapsed and there’s no going back to the family farm because the bank owns it now. But at least the nuclear family is still together and can form new family bonds with their close neighbors.

Enter World War II.

If WWI was bad, at least people believed it was “the war to end all wars”. WWII convinced the survivors their sacrifices had been in vain. The Lost Generation struggled to stay out of it until they were dragged in, then they sent their children, the Silent Generation, to die in another futile war against the same enemy: Germany, this time on steroids, plus a new enemy: Japan. These two brutal regimes showed the Lost Generation and the Silent Generation that humans were capable of true evil, and many came back scarred and broken from the confrontation.

These battered, ravaged souls who threw themselves into workaholism to feed their dying kids and lived on the edge of disaster gave birth to the Baby Boomer generation. They also craved freedom from the stifling inner city, and returning GIs were given incentive to build their own single-family homes. A single woman was now responsible for maintaining the entire household while a single man was responsible for funding every aspect of life. Cue the rise of “Mother’s little helper,” designer anti-depressants and anti-anxiety pills to help cope with the increased stress of isolated nuclear families who don’t have time to learn about each other or develop deep loving bonds.

How could these older generations possibly give Boomers what they needed to understand love, objective morality, warmth, nurturing, and family responsibility? Most Boomers barely knew their parents on the inside, down in their emotional core. We call the Silent Generation exactly that because they refused to talk about how they felt because they’d probably commit suicide if they stopped to think about all they’d endured and had taken from them. The Lost Generation and the Silent Generation gave themselves in near martyrdom to provide for their children, but the absence of larger family structures meant many Boomers went without those additional guideposts (grandparents, uncles, aunts) that would have taught them the value of love and family.

Some grew up understanding love nonetheless, seeing the deep sacrifices made on their behalf and recognizing what it meant. Many did not. Many Boomers resented the harsh disciplines laid upon them to prepare them for what the Lost Generation and Silent Generation knew were the secret horrors of the world. “Toughen up or you’ll die” could be an exact quote from these older generations, but to the Boomers, the strict rules from absent parents who came home exhausted and angry and barely had time for their kids smacked of draconian totalitarianism.

“You can’t tell me what to do, old man,” became the rallying cry of the Boomer generation. The movie Grease embodies this, and we start to see the true rise of the antihero.

The antihero differs from the dark hero and the classic moral hero because the antihero doesn’t care about morality. The antihero doesn’t want to overcome his flaws, he wants to be left alone. They reject love because they don’t understand it and have only known crushing oppression and abuse from those who should have loved them. The antihero rejects everything the moral hero stands for because the moral hero is full of crap and doesn’t know how the world really works, man. You don’t know me, dad. Get off my back. I can grow my hair out if I want to. What are you gonna do about it?

The antihero thumbs his nose at everything he’s told to embrace because everything around him is a lie only upheld by stupid people and hypocrites. This is reflected by many members of the Boomer generation who were preached at about the importance of family while they felt unloved in their own homes, largely ignored by exhausted and traumatized parents apart from occasional beatings or lectures on how stupid they were for the dreams they had.

The antihero soaked into the broken Western culture like water into a dry sponge. Old heroes still existed, as we see in many Disney films, because people still wanted their children to grow up believing in the good messages. Boomers at least were raised with traditional values and sensed intrinsically that the messages were good ones for kids to hear, even if the modern world didn’t reflect them. Boomers did their best to instill in their kids these moral messages they didn’t actually believe in but wanted to believe in because Boomers do love their children, even if many don’t understand what love really is or should look like. Many Boomers didn’t learn from their parents what love was or how to provide warm nurturing. Specifically here, look at Christianity and how the rules were beaten into people while the loving spirit behind them remained untaught. Religion became a thing of oppression and laws to follow or else rather than a system designed to assist a person in living a satisfying life.

Many Boomers were sent overseas to watch their friends die in endless political wars. When they complained to their parents, the Silent Generation (also called the Greatest Generation), they were told that’s how life works, suck it up and deal with it, because we did it and it was way worse for us, you don’t even have to deal with artillery shells. It’ll build character.

These new wars bore their own horrors and had the added element of fighting against political entities not actually attacking the US but working out political differences in their own countries (albeit with some atrocities committed against their own people). Lives were spent as political currency on distant shores without much obvious threat to the Boomers’ homeland, while meanwhile they lived under constant perceived threat by a mysterious superpower lurking in the shadows: Russia. These two separate and yet nebulously connected things, the Cold War and the endless hot wars it spawned against Communism, did little to endear authority to Boomers who came back scarred from what they’d witnessed. And when they arrived home, the Boomers who didn’t fight spat on the returning Boomer soldiers, cementing a hard divide within their own generation and teaching both sides to hate each other and the authority which had pitted them against each other. That bitter divide remains today as they battle over the smallest thing, playing politics and fiddling while the world burns and their children commit suicide.

Add in the rampant divorce rate as the loving Boomers married damaged Boomers and their marriages tore in half at the difference in definitions of love. Antihero fans married moral hero fans and the two don’t mix well. Antiheroes by nature must reject moral heroes. Moral heroes are either a complete lie, or the antihero is wrong, and antiheroes can never accept that they’re wrong because good is always a lie, so the moral hero must be stupid or lying.

Attachment formation is massively splintered at this time and only accelerates in each generation.

Gen X is raised by divorced or divorcing parents who preach morals they don’t really believe in and religions they don’t follow themselves, and extended family units are simply a thing of the past to be seen only in sitcoms on TV.

Gen Y comes next when divorce has become the new normal and leads into technology like video games, a glut of entertainment, and easily accessible pornography as a balm for emotional pain.

Millennials come along when birth out of wedlock is the new normal and love itself is a complete myth only seen on sitcoms, something to be ached for but never attained. Technology completely replaces many things for them including ambition to grow or change, and wounded individuals can seek out other wounded individuals in secret online and deepen their wounded beliefs instead of healing them. Many Millenials don’t even believe they’re worthy of love, giving rise to an even darker antihero who now rejects all forms of love and is never accepted by anyone, spending the entire story alone and ending alone.

A Millenial antihero is much closer to a villain, spends the entire story refusing to do what’s right but is forced to against their will, somehow connects to another person romantically but probably doesn’t cement the relationship, and leaves at the end so they have no responsibilities or connections, although the door is open so their romantic interest can wait indefinitely for them.

Millenials needed antiheroes who reject everything because they see themselves in these characters, not as a role model for how to act, but as validation for what they feel. This is why later antiheroes rarely end up married with kids at the end of the story. That sort of ending for their own lives feels wholly unbelievable for Millenials. No, they need to see the antihero just as alienated at the end as at the beginning, but now everyone else recognizes their worth and wants them around. Now the antihero is an outcast by choice, not by rejection.

How many stories have you seen lately where the antihero is a perceived villain for most of the story but then saves everyone and is finally validated by the leaders of the stupid hypocritical society and told “We were wrong about you and now you’re being offered this huge honor” and the antihero says “No thanks, I’ve got my happiness, leave me alone, get away from me, I’m gonna go wander off” while their love interest stands there smiling watching them leave and thinking how wonderful they are?

Millennials need the protagonist to still be alienated at the end. They don’t like it, but they need it, otherwise it just doesn’t feel real, that’s just too Hallmark, real life isn’t like that at all, no one can be loved and accepted, happy families just fall apart anyway, better to stay alone.

No, the real treasure is emotional validation which the antihero can now reject and feel even more validated.

Leading to Gen Z. Often called “The most conservative generation since WWII”, or “Zoomers”, Gen Z kids have never seen healthy extended family networks, don’t understand the last hundred years of decadent slide toward insanity and fear of love, but grow up saturated in a culture bleeding to death from unmet needs. Many collapse into desperate attempts to seem interesting or worthy of attention, but many more quietly bide their time and observe the world around them.

What many Zoomers learn is that love, family, freedom, and morality are utterly rejected by the broken parents abusing them or neglecting them in pursuit of desperate hedonism as escape from emotional pain. Zoomers are disgusted by their own recent ancestors and are looking for a better system to get out of this sucking swamp of degeneracy and hopelessness. Gen Z is committing suicide in the droves because their situation is sink-or-swim, a desperate meat grinder to find meaning in a bleak world devoid of love or hope. Those who stand firm look to the distant past, before WWI, and find lost threads in ancient religions and honor codes.

Most storytellers active today fall into one of these generations. We’ve watched the slide from classic moral heroes to dark heroes to antiheroes to villains masquerading as antiheroes.

But antiheroes are exhausting. They were initially edgy and unique but are now becoming played out. Zoomers are largely rejecting modern antiheroes. Ticket sales, merchandising, and modern book sales are struggling. The market bears this out.

We’ve looked at the generational trends and some of their preferences. How does what we know impact the market so we can predict what comes next?

Attachment as character depth

The most compelling characters most of us recognize as popular have deep attachment problems. This can come from parental rejection, evil parents, a dead parent, two dead parents, childhood trauma, or any combination thereof. Somehow the character grows up missing an element of love and family, but craves the missing things.

Classic heroes before 1900 had small elements of these but pushed through them unflinchingly as they unquestioningly drove toward morality. They sought to achieve moral character in spite of their attachment wound, or were even inspired by attachment problems to feel a deeper drive toward morality to make their ancestors proud of them.

Dark heroes from the Lost Generation and Silent Generation ignored the attachment problems and drove toward morality with a few questionable acts we handwaved along the way because we saw their golden heart and still admired them.

The original antiheroes from Boomers started with deep attachment problems but somewhat begrudgingly overcame them and found the loving families they craved.

Darker antiheroes from Gen X and Gen Y started with deeper attachment problems and embraced them to define their own rules, coming in at mixed endings with some level of personal happiness but usually retaining their attachment wounds.

Millennial antiheroes begin with soul-crushing attachment problems, refuse to fix or change them, only begrudgingly accept any kind of warmth from others, and end the story alone by choice as everyone else learns the antihero was secretly awesome all along and validates them so the antihero now gets to reject society from a place of power. Put another way, Millennial antiheroes embrace their attachment wounds as truth without fixing them.

Attachment problems form the core of many interesting flaws a character can have, but the classic storytellers used these attachment issues as vehicles to teach why healthy attachment is so important by exploring our innate craving for love and what happens in its absence. This element remained in Gen X and Gen Y which is why audiences saw the rise of so many sympathy villain pieces where they only acted evil because they craved love and never got it. These villains stopped being villains and became the heroes for Millennials when the next generation stopped believing it was even possible to be loved in the end.

Let’s talk about what comes next.

What antiheroes get right, why they’re exhausting, and why GenZ is rejecting them

Zoomers split the antihero/classical hero divide wide open.

The Zoomers suffocating under nihilism revel in antiheroes who end up stomping society into the ground and urinating on it for good measure, then leaving to live alone in a palace made of ice where they get to make all the rules. This audience is largely collapsing into an epidemic of drugs and suicide but are the targeted audience of most large media companies. Many argue there’s a political and international reason these stories are being pushed so hard in the mainstream and normalizing hedonism and nihilism, but I’ll leave that discussion to smarter folks so we can focus on the audience aspect alone.

Instead, I’ll say that these sorts of antiheroes are easier to write because the writer doesn’t need to understand anything about real love and doesn’t need to craft a story where the character’s beliefs are challenged and then changed. It’s easier to validate an existing belief than to frame a story around an argument for why that belief is flawed. It’s harder to show a compelling reason for changing oneself to be healthy when the writer themselves doesn’t believe there’s a compelling reason or a true healthy way of living.

Nihilism in the creator almost universally leads to nihilism in the work.

The majority of Zoomers seeking tradition are rejecting these sorts of antiheroes. Zoomer heroes on this side of the divide are returning to the classic moral view, of absolute justice and morality regardless of what they face. Zoomers don’t seem sure yet if a hero should end with a happy family or not because they don’t know what that looks like, but they’re incredibly happy when they do see that kind of ending.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Harry Potter. Yes, that oft-reviled series actually strikes the Zoomer chord perfectly because (spoiler alert) despite beginning with agonizing attachment problems, he chooses to be a moral hero, abandon his flaws in favor of becoming a better person, builds a new adopted family, sacrifices himself out of love for others, honors his parents and wants to make them proud, and in the end gets married and has children with someone he loves.

I submit that Harry Potter strikes a chord with Millennials because he’s secretly what they crave to become but don’t believe they ever can be, but he also embodies the new Zoomer mentality of what a hero should be, because he was made by someone from GenX/GenY who still retained that secret hope. Harry Potter is the perfect blend of the last 4 generations with an eye toward what audiences will likely want in the future. And Millenial creators will likely struggle to reproduce a character with his depth and appeal because most of them no longer accept or understand the elements which make him universally beloved.

There’s a reason humans innately love morally upright characters, and it’s because storytelling was originally a vehicle for teaching codes of behavior and life lessons. We seek role models to tell us how to live. Storytelling now is split between that original purpose and validating attachment wounds. Validating attachment wounds may make people feel good in the moment but is specific to each generation as far as what they’ll accept and reject, while objective moral heroes stand the test of time, even across thousands of years.

And Zoomers, the ones who are surviving and thriving, seem poised to bring back everything traditional. Morality is in vogue once more, as are responsibility, family, love, and honor.

All of this woven together leads me to believe that the future of popular protagonists will follow the Harry Potter model.

Begin with an attachment issue and a reason they feel unloved.

Show them craving that love, even if they lash out at others in their pain.

Include warm loving support characters who give them unconditional love.

Show the protagonist slowly learning to accept real love rather than having those loving characters turn out to be secret hypocrites who betray them.

Make the love real and show the audience what that feels like as the protagonist grapples with what it means to be loved in such a way.

Show the protagonist working to overcome their attachment problems rather than collapsing into them.

End with the protagonist embracing love and morality rather than rejecting it out of spite or nihilism. This ending takes place after the overall plot is resolved and forms the “true” ending with the “true” conflict, the need to be loved which has underpinned the entire adventure and is actually more compelling than the need to stop the villain.

All of these things can work as excellent side plots to your end-of-the-world epic and deepens the characters from 2D to 3D, from static to dynamic. It also fleshes out the word count, if you’re into writing longer works, and can act as a great overall conflict in an ongoing series. The protagonist not only battles the evil arch-villain but also their own inner need to be loved.

Memorable characters are made from this material right here, from an audience who doesn’t understand love being able to read your story and say “THIS RIGHT HERE is how you be a good friend! Oh, THAT’S how you love a partner! WOW, I wish my parents had acted this way, this is exactly how I’ll talk to my kids!”

The takeway

You’ve stuck with my ramblings for this long, so I’ll summarize it like this:

Millennial-style antiheroes are on the decline for audience engagement, likely won’t move many units, and will probably provide even fewer returns as time goes on. If you want your stories to appeal to the newest audience coming into their own and to have universal appeal, learn to shift your view of attachment problems in stories and how you handle them. Have your cast of characters begin with attachment issues but work earnestly to overcome them as they grapple with what it means to be loved. Show that love developing. Misunderstandings and tragedies can occur but should be resolved, not left to fester and display the secret truth of nihilism. End your stories with love and acceptance, not rejection on either side.

The next generational audience craves the return of truly moral heroes who embrace honest love. Show them what that looks like.